Takashi Murakami, Superflat, and the Aesthetics of Superficiality

Teachers are fond of unanswerable questions. Just roll them out and hold court as the pupils debate. When the designated time arrives, an instructor will turn, feign a sigh, and announce “Well, I guess we have to agree to disagree.” As the last student files out, the faintest grin peels across the face of the teacher, akin to the final scene of a heist movie where the protagonist boards a bus with a heavy duffle bag. One beloved unanswerable is “What is Art?” This question may be the central dynamic in modern art. Is it the supreme expression of technical skill or the deft control of context and narrative, the classic urinal sat in a gallery. Evolving out of 20th century debates began in Europe, these discussions take on a completely difference valence when applied to Africa, Asia, and Latin America. For example, the Cubism of Picasso was famously inspired by African masks he discovered in an ethnographic museum, then cast as primitive art. This later left many to wonder about the distinction between the sophisticated and the vulgar in artistry, especially in regards to the supposed pinnacle of Western art. Takashi Murakami, who became the face of Japanese contemporary art, mulled over this question of “What is Art” and spat it back in the face of the Western art establishment to dramatic effect, although it is unclear if his spectacle had any lasting impact.

Takashi Murakami was born in 1962 and attended the prestigious Tokyo University of Fine Arts, earning a PhD in Nihonga (Japanese art). I first learned of him in 2007 when he was commissioned as the cover artist for Kanye West’s Graduation album, as well as a director for a music video for the opening track on the project. It is arguable who was bigger at the time. Just as West was reaching a sort of culmination of his pop stardom, Murakami was simultaneously experiencing his own kind of consummation as king of the Japanese art world, at least through the eyes of the West. By 2007, Murakami had exhibited his work in a number of galleries in Japan, the U.S., England, and France, including multiple times at the Museum of Contemporary of Art in Los Angeles. With a long standing collaboration with Louis Vuitton, a studio workforce of more than a hundred people, and the sale of one of his works for 15 million dollars in 2008, he came to be seen as a high-art manifestation of the manga and anime wave then inundating the West.

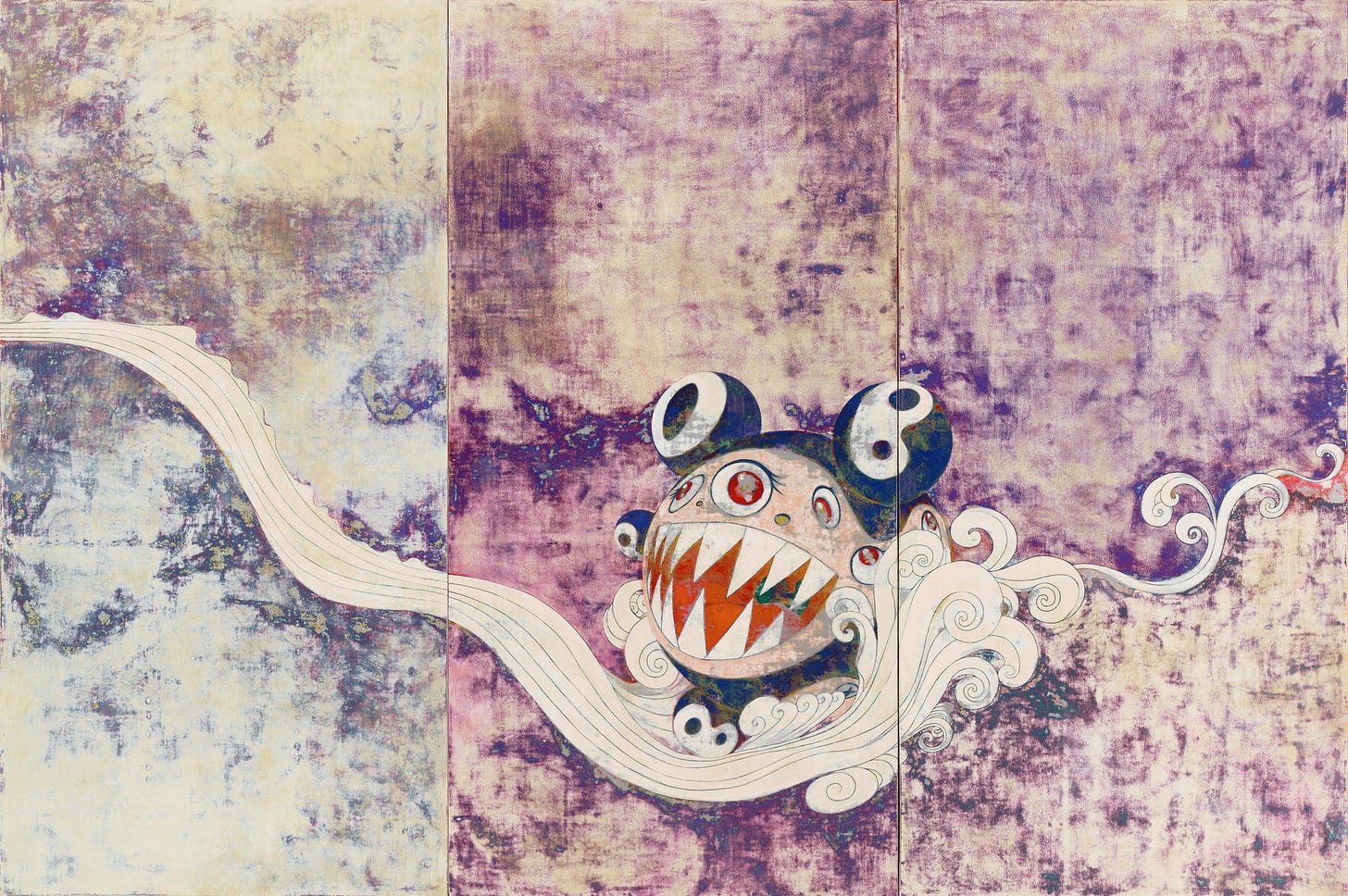

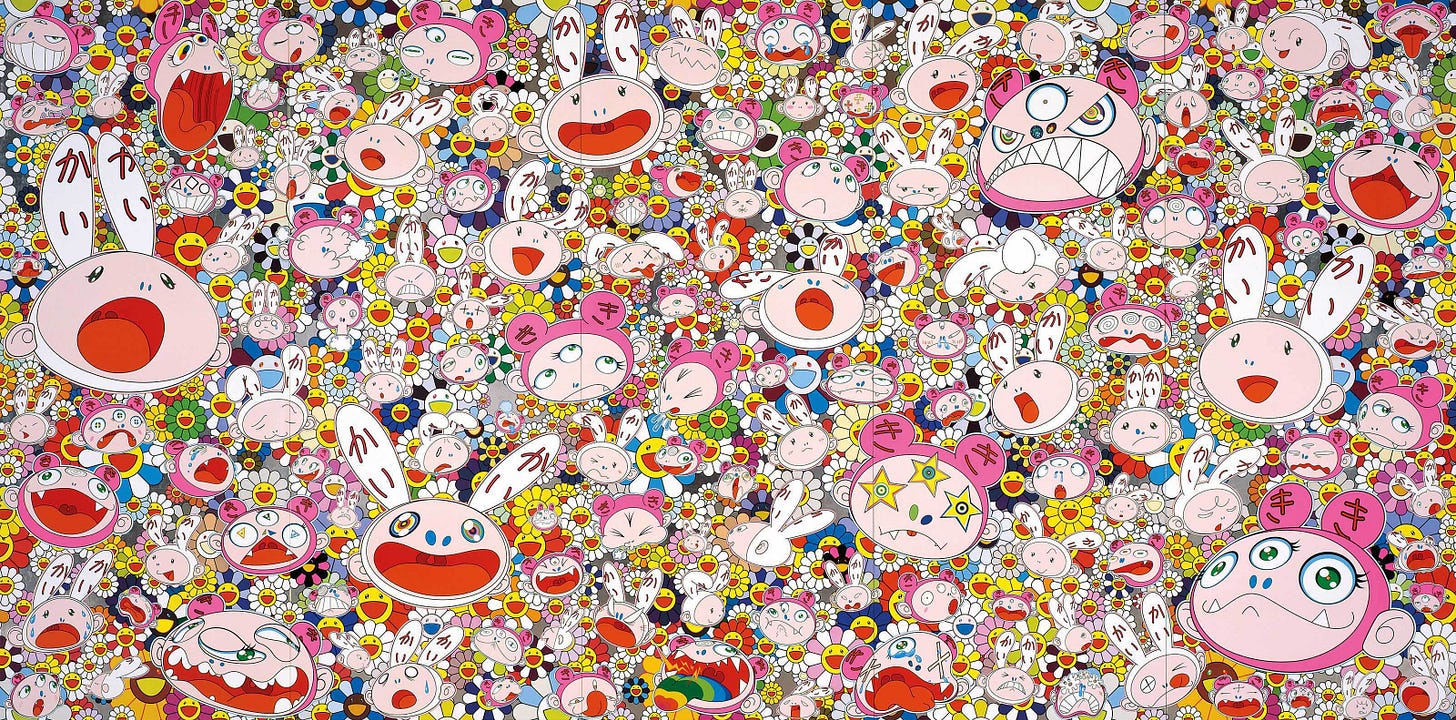

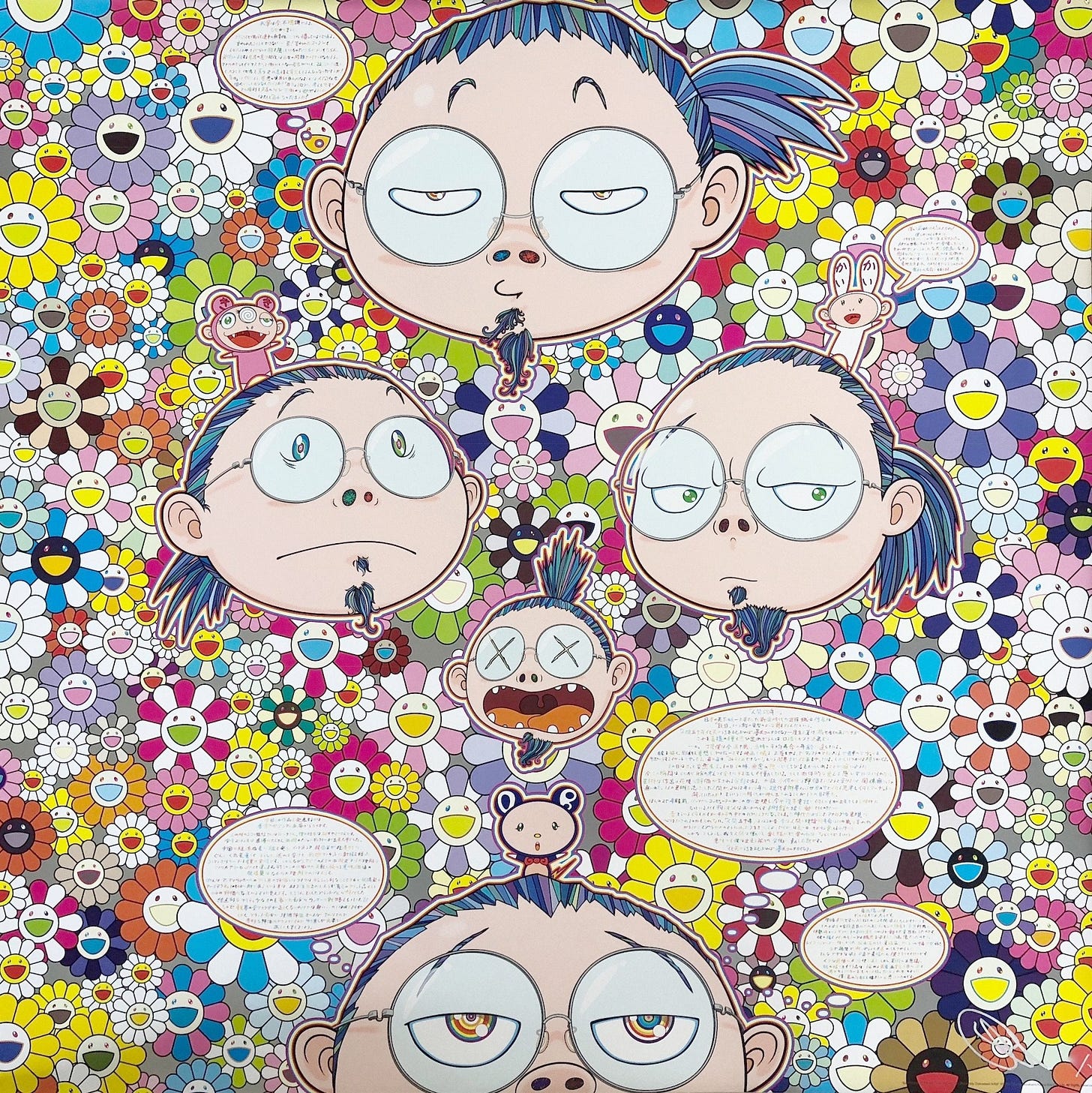

Murakami was the main proponent of an artistic philosophy known as Superflat. He argued that Japan, unlike the West, had very blurred distinctions between high and low art, or perhaps “Art for Art’s sake” and entertainment. Murakami pointed to the success and critical acclaim of manga artists and animators such Hayao Miyazaki. Without this hierarchy of art forms found in the West, Japanese art was philosophically “flat”. He extended this “flatness” to the actual visual presentation of Japanese art, which has historically eschewed the use of shadows employed in the West. Along with the continuity of past and present in Japanese art, the ubiquity of art in Japanese society, and the rapid transitions displayed in anime and manga, Japanese visual culture is collapsed into a single entity that is superflat.

In practical terms, Superflat art consisted of the themes, content, and forms associated with otaku culture, or “all-consuming nerdom”, particularly an obsession with Japanese teen culture, abject cuteness, and idol and brand worship. Originally, the term otaku had negative, or even deviant connotations in Japan, so Murakamai self-consciously raising its subculture to gallery level artistry was an act of transgression. This may have made his superflatness claim more prospective than definitive. Nevertheless, by this point in history, with his ability to sell kawaii figurines at Sotheby's for hundreds of thousands of dollars, the otaku identity has become global and salutary, and Murakami may have had an active hand in its evolution.

Although Murakami released a self-serious manifesto explaining Superflat, the whole endeavor may have been tongue-in-cheek. He has occasionally drawn the ire of those inside and outside of Japan for selling the West an exoticized version of Japanese art, drawn from an outcast subculture. Murakami has hinted as much, gleefully presenting an image of Japan as adolescent, feminine, and strangely perverse, with Western art buyers willing to consume such visions at inflated prices. This may be his way to get back at the West for undervaluing Japanese art. As with Andy Warhol, Murakami offers the possibility and allure of being duped, which is seemingly its own art form, one that is very much appreciated around the world. Along with his contemporaries, Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, and whose art seems to exist somewhere between spectacle and tech start-up hoping to be acquired by Google, at this moment of history true artistry may simply be the manipulation of the finance and corporate branding.